Descifrando relatos anudados

This work is based on the sound activation of the knots of the object Khipu (Inca counting system) which contains the voices of a group of female migrant students of the University of the Arts Bremen to make visible and share their stories about what it is to be a migrant and how this feel from the practical, the social, the emotional, the distance and the affections.

Known as the first Andean textile computer, a tangible interface encoded in knots and strings of cotton and wool, the khipu was used as an accounting instrument in South America, first by the Wari Empire (600-1100 AD) and then by the Inca Empire (1400-1532 AD) until the arrival of the Spanish colonization, which led to the disappearance of most of the khipus due to the cryptic nature of their language, which went against the Catholic Christian beliefs.

They were used to record demographic data, taxes, inventories, ritual offerings and other similar information. However, there were also narrative khipus that were used for biographies, stories and poetry about Inca’s life, as Garcilaso de la Vega (1688) confirms: “Treating their knots as letters, they chose historians and accountants… to write and preserve the tradition of their deeds using the strings of knots and colored threads, using their stories and poems as an aid”. The latter are the ones that inspired me to do this work because of their unique quality as message carriers.

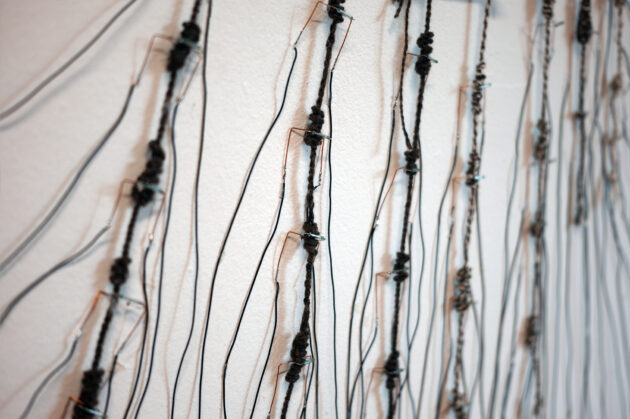

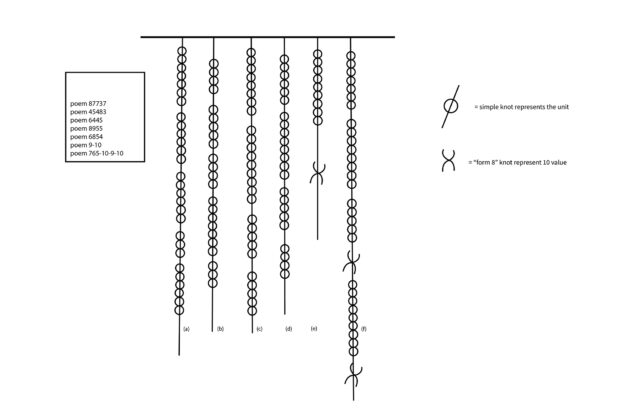

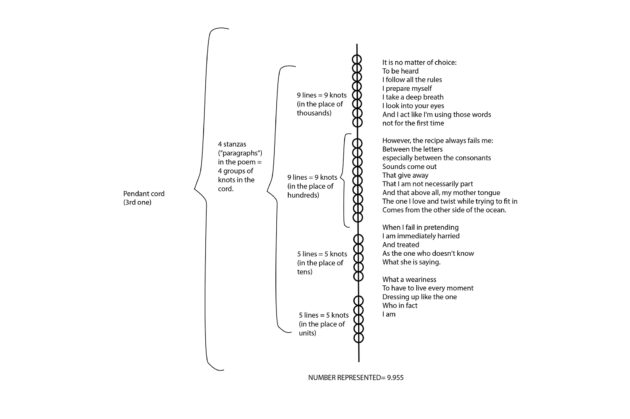

Most khipus are formed by a main horizontal string, from which hang subsidiary strings that have groups of knots tied along them, which encode numerical values following a decimal system. Because of their level of complexity, khipus are now considered textile computers, as they encode anything through sequences of 0’s and 1’s. It also symbolized ideas through intrinsically binary chain features, such as S or Z knots, clockwise or counterclockwise layering, and cotton or animal fibers.

I decided to “encode” the stories of this khipu as poems inside the knots because the poems are made of verses and stanzas that respond to the numerical logic of the khipu. Therefore, each hanging string represents a poem written by one of the participants, in the same way that the number of knots in a string will represent the total number of lines in the poem.

The poems represent their feelings, experiences, stories, thoughts and reflections drawn from the personal migratory experience of each of them. They are intimate and personal, but have in common the fact that they all made the decision to leave their country and not return, where the need for a deep-rooted identity is activated when faced with what does not belong to them, with what generates emptiness and seeks to find a meeting point somewhere. A point that could be found by identifying with the other through empathy.

Using the khipu to make audible and transport these stories is an attempt to re-signify the sense of origin of identity and appreciation of South American indigenous roots, since the participants are women who come from different parts of Latin America. This need for reunion is born with the intention of recovering ancestral knowledge that values the feminine sense of life and that was denied and demonized due to power conflicts and the imposition of the Catholic patriarchal order after the Spanish and Portuguese invasion.

This simple fact triggers questions about identity, an identity that was annihilated and that today is questioned in various ways in countries where indigenous peoples still manage to survive and where women continue to fight for their rights. Therefore, the preservation of the wisdom transmitted by them acquires a critical importance in times when the conservation of nature becomes an imperative.

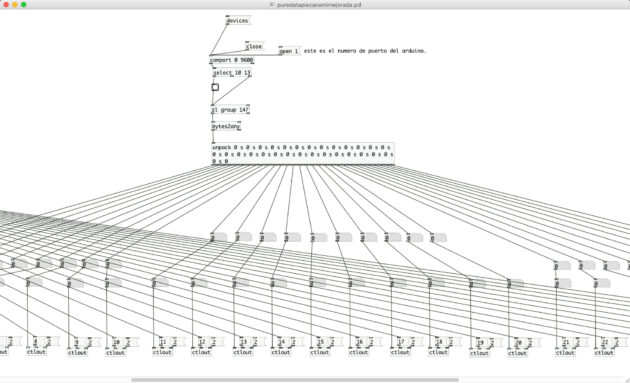

For the khipu to start counting the poems encoded in its strings, it is necessary to activate the knots with a metal stick placed along the right side of the ancestral knot weaving. Thanks to the fact that the stick contains a magnet at its end, it will send the signal to the sensors of each group of knots to start reciting the lines hidden in them. In the past, khipus were only read by the Khipucamayos (experts in reading khipus) due to the complexity of their language. Hence the relevance of the use of sensors as a special technology to help us listen to the information stored in them. The words emerge from the loudspeakers, enveloping the space with the women’s voices. Some of them did not want to use their voices, so they were asked if someone else could recite their poem.

References

De la vega, G. (1688). The Royal Commentaries of Peru. https://archive.org/details/royalcommentarie00vega